Culture

Thirst For Salt Is A Different Kind Of Love Story

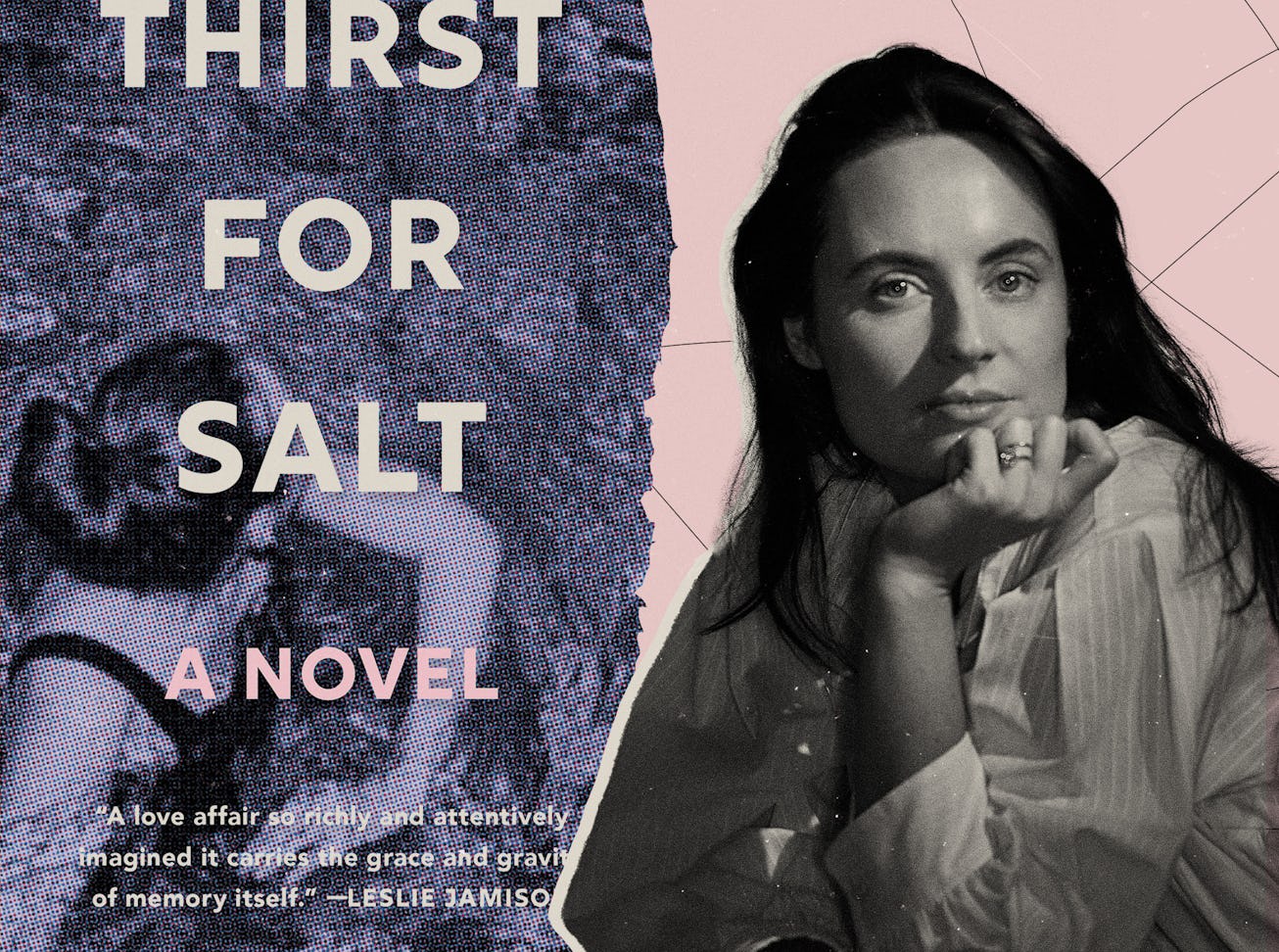

In her debut novel Thirst For Salt, Madelaine Lucas explores love's sandy gray areas.

Thirst For Salt is a love story. It’s not a love story told in sweeping declarations or with promises that love will conquer all, but one consumed with pleasure – and not even the carnal, so much as tiny, exquisite intimacies; lovers licking mango sprinkled with lime and chili salt off each other’s faces in bed, drinking glasses of wine as decadent as a whole meal, sleeping with grains of sand between the sheets. Most of all, it is a love story not so much about how people come together as how they fall apart.

To try to answer this question that spawns a million more, Madelaine Lucas almost worked backwards – writing the love story from the perspective of a woman who is 13 years past it. From the first page, we know the relationship is not going to survive. In fact, we know it’s brief. But that doesn’t make it not worth telling. For Lucas, what’s compelling is the slippery nature of love, no matter how much of it exists.

“I used to really spend a lot of time thinking about love; I think it's one of the most profound human experiences. It's pleasure and it's pain,” Lucas says over coffee in Brooklyn. “When I started writing the novel, I was really interested in this question of ‘Why do people come apart, and why do relationships end?’ I was really energized by the idea of heartbreak as a fundamental experience that I think raises so many other existential questions about grief, about memory, about longing.”

Lucas’ debut novel chronicles the relationship between Jude, 42 and an unnamed narrator, 24 – who “marveled at the symmetry of our ages” – who meet while she is vacationing with her single mother at Sailors Beach in New South Wales, Australia, off the coast of the South Pacific, after finishing college. She meets him while swimming in the ocean. Later, on the beach, he calls her “Sharkbait,” and brings her back to his house to nurse her wounds after she’s stung by a bluebottle jellyfish. She sneaks off every night to see him for the rest of the vacation; and afterwards, eventually moves into his old house, a rustic A-frame surrounded by wilderness, by blue gum trees and lorikeets, and covered with paperbacks and antique furniture he restores. They adopt an ancient dog larger than her and name him King.

The addictive intimacy of the novel isn’t in the characters’ desires for each other, but in the quieter retelling of the details of the relationship; the more mundane, the more wonder they hold. The inheritance of their relationship is chronicled not through years spent together, friends made together, whether or not there was a child, or a marriage, but in their tiny, sometimes claustrophobic domestic routines: getting dressed under covers, mixing powdered milk into tea when the power goes out; peeling oranges by the sink, ice melting in whiskey, crusty fish cooked in salt.

Things aren’t perfect, because they never are, and it’s easy to blame the age difference. But though it’s a source of tension, it is not a story about an older man and a younger woman in the way these kinds of stories are usually told: cautionary and exploitative. Jude is withholding, but he is also staunchly devoted; things are not so black and white. For Lucas, pleasure is the greatest equalizer. These characters give and take like the salty tides where they first meet.

“I realized that the power couldn't just go in one direction because then it would be static, and that doesn't feel true to any experience of intimacy that I've had,” Lucas says. “The younger woman, older man dynamic is such a trope. I did really want to bring nuance to it. It felt really crucial that the book be driven by her desire for him, as much, if not more so, than his desire for her. Her pleasure is so central and if it's there, then that says something about their relationship. If it's absent, then that raises other questions.”

As a result, Lucas has drawn a richly psychological study of love that doesn’t rely on clichés or standard power imbalances. That’s also because there aren’t just two, but three hearts beating at the center of the book: that of the narrator’s young mother, with whom she is extremely close, the roles of parent and child more suggested than compulsory.

With a cartographer’s precision and an explorer’s fearlessness, Lucas charts the blueprints for how our early experiences of parental love affect our own relationships. The novel is not autobiographical, but this way of thinking about love, almost backwards, dissecting it from the end to try to find the holes along the way, comes from Lucas’ own experience with her parents’ relationship.

“My parents, also like my narrator’s, divorced when I was very small, and I grew up in the shadow of their love story – which was very romantic, but tragic to me because as long as I can remember, I knew that it didn't last,” Lucas says. “I think especially coming of age as a young woman, you're so influenced by your mother's story and the choices she made. Whether you are actively trying to choose those things, or avoid them, you can't help but be haunted by these potential partners or repetitions.”

Because of this, the narrator’s relationship with her mother is just as central as that of her and Jude’s; her mother’s own life a constant litmus test for her own. And in a similar way to her own mother’s young motherhood, the narrator deeply contemplates a child, longs for some semblance of permanence in her relationship that feels so destined to be temporary.

“What I longed for was a guarantee that if this love ever ended, at least there’d be a record of it , outside of the two of us and our two bodies,” Lucas writes. “Though part of me knew, of course, that it could never work like that – what a burden to put on a child. Had I not seen my own father’s eyes fill when he looked at me when I was a girl, any time an expression crossed my fave that resembled my mothers?”

In a culture that wants to define relationships as successful or unsuccessful, Thirst for Salt lives in the salty, sandy gray; where relationships, even so-called failed ones, don’t exist in broad strokes but in tiny, prismatic specks of light. Because when a relationship ends you’re supposed to contract amnesia for all the good things about it. The narrator, decades later, resists temptation to ignore the weight the relationship had. Instead she gives it the weight of everything, of her whole heart, which no matter how it ended, is what it deserves.

“I don't know if it's possible to really get over them in the way that we're told that we have to,” Lucas says, and I’m not sure if we’re still just talking about the book. “They just become part of who we are.”